The desulfurization of distillate fuels continues this year. Before the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulation began in 1993, US diesel fuel contained up to 0.5% (5,000 parts per million or ppm) sulfur. EPA began phasing in more stringent regulations beginning in 2006, requiring 15ppm Ultra-Low Sulfur Diesel (ULSD) for road vehicles in 2010. Nonroad diesel fuel standards from EPA tightened to require 0.05% (500ppm) Low Sulfur Diesel and then ULSD for nonroad, locomotive, and marine (NRLM) diesel. Home heating fuel diesel limits began tightening in the US Northeast with the state of New York requiring ULSD in July of 2012. Over the subsequent years, most Northeastern states followed suit. This summer, Maryland is moving from a 500 parts per million (ppm) sulfur specification for home heating to the 15ppm ULSD specification. As of this writing, it was unclear whether or not Pennsylvania was moving to ULSD – this would be last remaining Northeastern state not using ULSD (and only partially, as Philadelphia has already switched to ULSD). With this chapter closing, a new and potentially dramatic chapter in distillate fuel desulfurization is coming next year, when the new IMO 2020 rules requiring 0.5% (5,000ppm) sulfur marine fuels come into force.

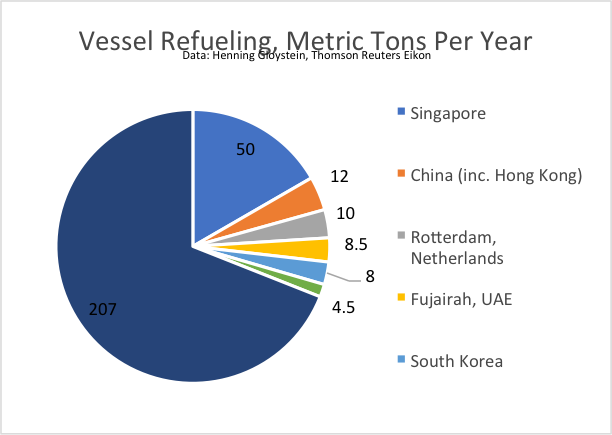

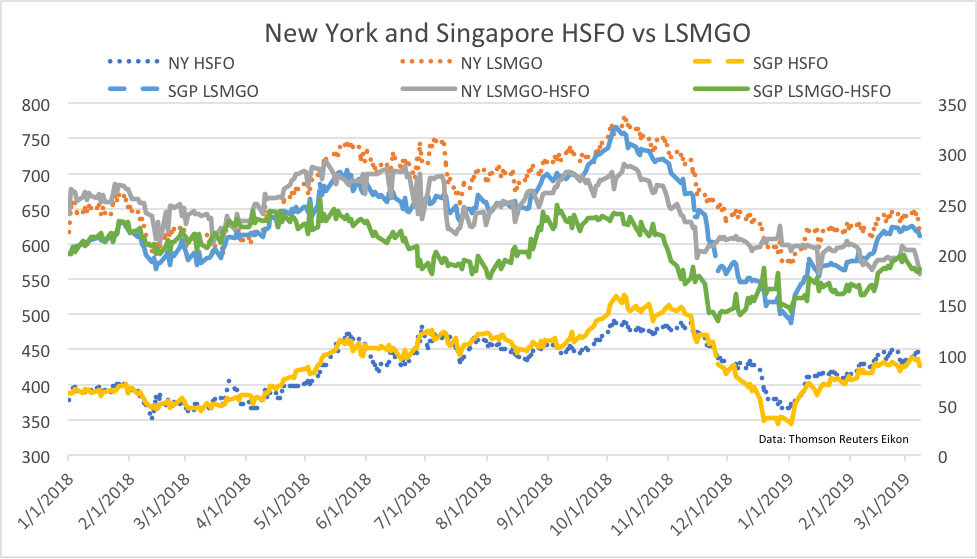

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL Convention), which came into force in 2005, with Annex VI restricting sulfur oxide (SOX) emissions. Beginning on January 1, 2020, the sulfur limit for fuel used by ships operating outside of designated emission control areas (which remain at 0.1% or 1,000ppm sulfur) will fall from 3.5% (35,000ppm) to 0.5% (5,000ppm). In order to comply, ship owners will have to either run the more expensive low sulfur fuel, install expensive sulfur scrubbers, or fail to comply. In the longer run they could also convert to run on Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). Scrubber adoption will depend on consumption and the spread between low and high sulfur fuel. As Singapore is easily the top port globally for ship refueling, the HSFO-LSMGO spread at this location is of particular interest. Scrubbers are expensive, and so 100% adoption is highly unlikely, meaning demand for low sulfur fuel is likely to spike.

The head of the oil industry and market division at the Paris-based International Energy Agency says he believes the “industry has already passed the date beyond the smooth transition” to the implementation of IMO 2020. McKinsey & Co. estimates global consumption of high sulfur fuel oil (HSFO) was 3.5mb/d last year, and Goldman Sachs puts demand at 3.3mb/d in 2017. Norway’s SEB Bank says some 3mb/d of demand for HSFO will “disappear overnight” due to IMO 2020. Low apparent scrubber adoption indicates the transition could, indeed, be disruptive. Manufacturing firm Wartsila puts the cost of scrubbers at between $1m to $6m, pricing this option out for many ship operators. Although IEA estimates some 2,000 scrubbers could be installed – adding 340kb/d of HSFO demand in 2020 over 2019 – this will have only a marginal effect, and most ships will have to shift to a lower sulfur fuel. IEA predicts that demand for HSFO could fall by 60% next year, from 3.5mb/d to 1.4mb/d.

Very Low Sulfur Fuel Oil (VLSFO) is being developed in order to meet the IMO 2020 regulations, but production is seen limited initially, with the additional problem of varying quality by supplier. Most incremental shipper demand will therefore likely be for Low Sulfur (0.5%) Marine Gasoil (LSMGO/DMA), which is widely available but more expensive, and according to Shell brings thermal shock and lubricity issues. To meet this greater demand, refiners will have to raise low sulfur gasoil production. IEA expects global gasoil production will increase by 2.3mb/d by 2024. This will not be without cost, however. In order to increase low sulfur distillate yields, refiners might need to install new hydrocracking and coking units, an upgrade that could cost $1bn. Consultancy KBC estimates 40% of Middle Eastern and European refineries are not prepared. Another option is to buy sweeter (lower sulfur) crude oil feedstock, but this trades at a premium to sour. US Gulf Coast refiners, due to their relative complexity and access to ample light, sweet shale oil production, are relatively well poised.

A final option for shippers in noncompliance. Estimates of how much cheating there might be vary, from as low as 10% to as high as 40%. IMO aims to ban ships that do not have scrubbers from carrying HSFO, making it easier to identify cases of noncompliance. While noncompliance may dull the impact of the transition to some degree, it is still likely to be disruptive, not only for refiners as previously mentioned, but for many other sectors due to higher shipping costs. Wood Mackenzie estimates global shipping fuel costs could rise by 25% or $24bn next year. Additionally, the jump in distillate demand is likely to support jet fuel and diesel prices as well.